The Masters of Charterhouse have usually been distinguished men but not all of them have left a tangible record of their time here. Two 18th century Masters, however, have given us such a reminder. Both were of scholarly bent, were prolific authors, were suspected of being unorthodox in their theology and each was eminent enough to achieve an entry in the Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (ODNB)

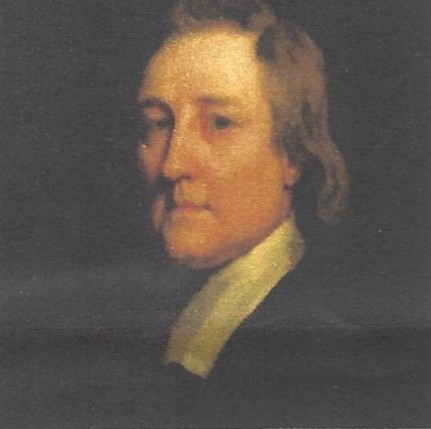

Every time we enter the Great Hall we see above us the portrait by Sir Godfrey Kneller showing the stern features of Thomas Burnet c1693.

Incidentally the ODNB wrongly states that the painting is at Charterhouse School.

Burnet was a Yorkshire man. He was born at Croft c1635 and he died 300 years ago on 27 September 1715. He was educated at Northallerton and then at Clare College, Cambridge. He was a disciple of the Master, Ralph Cudworth, and he moved with his mentor to Christ’s College when the latter changed his allegiance. Burnet became a Fellow of Christ’s in 1657 and he was Senior Proctor in 1667-8. He was, according to his namesake, Gilbert Burnet, ‘the most considerable among those of the younger sort’ of followers of the philosophy of Descartes.

Burnet was, however, often away from Cambridge. He travelled abroad as tutor to Lord Wiltshire. He seems to have left Christ’s in 1678 and moved to London. In 1681 his former teacher John Tillotson (the Dean of Canterbury) recommended Burnet to the Duke of Ormond as a tutor for his grandson, the Earl of Ossory. Ormond described him as being ‘a discreet and sober man’.

Furthermore ‘his conversation and manners were worthy of a clergyman in all respects.’ The Duke was Burnet’s principal sponsor in the election of the Master of Charterhouse. This took place on 29 May 1685. The Church hierarchy, however, were concerned that Burnet, although in holy orders, went about dressed as a layman.

As Master of Charterhouse, Burnet is mainly remembered for his role in standing up to James II in December 1686 and again in the following March. The King wanted to nominate a Roman Catholic, Andrew Popham, as a pensioner at Sutton’s Hospital. The notorious Judge Jeffreys vigorously supported the King but the Governors stood firm and defied the King’s wishes at their meetings in January and June 1687.Burnet reaped his reward at least to some extent. He was appointed Chaplain in Ordinary and Clerk of the Closet to William III in 1692.1

Doubts existed, however, as to the orthodoxy of his beliefs, and in Novembe1 1695 he resigned from his court duties to concentrate on Charterhouse.

The rest of Burnet’s time was relatively uneventful. He was a prolific writer.

He was careful to whom he dedicated his books. Recipients of his favour included Charles II (‘the Defender of our Philosophick Liberties’), William Ill (whom Burnet called ‘Hercules’) and Queen Mary. Joseph Addison and Richard Steele (his former pupils) paid tribute to his elegant style.

Much of Burnet’s work concentrated on the Biblical acounts of the creation of the world and of the flood. In correspondence with Sir Isaac Newton, Burnet maintained that the Genesis story of the creation was a sophisticated one, adapted by Moses in order not to puzzle the simple Israelites with philosophical truths which were not immediately obvious. Newton did not like this criticism of the veracity of Genesis.

This gave rise to the view that Burnet held.

That all the books of Moses

Were nothing but supposes

And when the serpent spoke , Sir,

‘Twas nothing but a joke, Sir,

And well invented flam

Later works by Burnet, including criticisms of Locke’s Essay concerning Human Understanding, were published anonymously. Burnet was unmarried. He died at Charterhouse on 7 September 1715 and was buried in the chapel. We remember him in this tercentenary year.

Burnet’s successor but one, Nicholas Mann, was probably born in Tewkesbury late in 1679. He was a King’s Scholar at Eton and proceeded in the usual way to King’s College, Cambridge where he became a Fellow as a very young man. He was tutor to William Godolphin, Viscount Railton, later Marquess of Blandford. He taught for a time at Eton but he also travelled extensively abroad.

He became Master of Charterhouse on 19 August 1737. At his institution he caused great controversy when he told the Archbishop of Canterbury that he was an Arian-that is one who denies the divinity of Our Lord. One wonders whether clergy of unorthodox belief like Burnet and Mann were attracted to Charterhouse because they would possibly be less subject to episcopal scrutiny there than in a parish.

Stephen Burnett