The article in the Banner met with some success. I had a reply from John Burnett, a descendant of Sir Robert. He has an identical cup which would have been handed down from his 2 x great grandfather John Fassett. I attach some photos of it. He cannot find any makers marks on any of the pieces. On the one hand he seems to have an additional “stand” or plate which has the same design on it as on the cup, but on the other hand the lid of our cup has been rather badly mended at some time in the past.

I had to be in London last week and I went down to Sir Robert’s home, Morden Hall. I believe it existed as a school and then Council offices for many years. Needless to say there was no sign of Sir Robert’s occupancy now, but it does have the “feel” of a house of that period. The Hall is a venue for weddings etc.

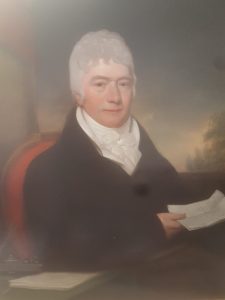

Sir Robert Burnett

Sir Robert Burnett

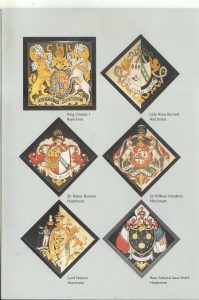

Antiques Roadshow came from Morden Hall Park a few weeks ,ago but the Hall did not appear. The Park has been separated from the Hall and is a “public place” and owned by the National Trust. The church in which Sir Robert’s hatchments are hanging with Admiral Nelson’s and Emma Hamilton’s, is close by, but it was closed. I called at what I assumed was the Vicarage and also the Parish Office but in vain.

Nelson lived at Merton Place, the “next door” estate to Morden Hall and for a time when Nelson was at the Admiralty, they used to travel up to London together because Sir Robert’s distillery was byVauxhall Bridge (in fact on the exact site now occupied by the MI6 building made so famous by the 007 films). One of the biographies of Nelson does mention Sir Robert as a guest at Merton Place.

He also had a house on the distillery site at 85 Albert Embankment . It was bought by the Anglo-American Oil Co. It was knocked down and the new 85 Albert Embankment is the MI6 address.

Probably Sir Robert’s most influential descendent was Marie Adelaide (1875-1960) m. Freeman THOMAS, 1st Marquess of Willingdon (1866-1941 as his wife she was variously Vicereine of Canada and then of India (1931-1936) during interesting times.

Another descendant is Sir Brian Burnett who was Chairman of the All England Club at Wimbledon. I attach a photograph of John and his cousin Bruce son of the late Sir Brian, during a doubles match at Wimbledon

John came to Crathes a few years ago with his brother Robin who sadly is no longer with us

The following may also be of interest. Thomas, [born 1612 in Braintree, Essex England died 1684], the brother of John’s 7xgreat grandfather, Alexander, went to America in the early 1600’s and settled in Southampton on Long Island. The ship actually landed somewhere near Plymouth, Mass. John was doing some research and found the following newspaper article from a few years ago:

He could scarcely believe how much the picture of Buddy Burnett looked so like his brother Robin ! Without telling any of the family anything about the picture, they all said it looked just like him. Amazing what genes can do …… and the family has obviously not moved for 400 years !

Burnett and Halsey: A Pair Of Old-Timers Recall Early Days As East End Farmers

Raymond Halsey and Buddy Burnett reminisce about Farm Life at Water Mill

The article by Michael Wright from a Southampton NY paper

When Raymond Halsey was a young man, there were some 50 family farms within the boundaries of the tiny hamlet of Water Mill alone, many of them—like his family’s—lying between the main road, now Montauk Highway, and the Atlantic Ocean. Today, Mr. Halsey estimates there might be four or five; one of the surviving operations is run by his four children, though—its organic crops sold at the Green Thumb farm stand, which Mr. Halsey and his wife, Madeline, opened 52 years ago.

Buddy Burnett remembers when Mr. Halsey and his brother Abram were trying to make their living as potato farmers and rented farmland on the edge of Mecox Bay from him in the 1950s. His father had grown potatoes on 109 acres on the western shore of the bay, running from Burnett’s Creek to the ocean. Today, it is the posh Fordune development.

“Harvesting potatoes was a terrible job,” Mr. Burnett recalled in the booming voice of a church choir tenor, referencing a time long before the work was done by machine. “You had to be on your knees all day.”

“Clear across to the bay and back—you couldn’t stand up,” Mr. Halsey added, with a gesture over his shoulder toward Mecox Bay. “On our second date, [Madeline] asked me, ‘Does your mother pick potatoes?’ Her mother had seen the kids working in the fields and told her: ‘Don’t marry a farmer.’”

“But that all got put to bed by my father,” Mr. Burnett continued. “He said, ‘Let’s build a mechanical picker,’ and that’s what we did—near as I know the only one in the United States of America at that time. A couple of summer people wanted him to get a patent for it, but he didn’t care too much about that.”

Mr. Burnett, now 91, returned to Water Mill earlier this year following the death of his wife, Marjoriee, and he and Mr. Halsey, 86, have rekindled their three-quarters-of-a-century-old friendship—meeting daily for coffee at the Princess Diner in Southampton. Both men grew up working the land in Water Mill, and both watched the farming industry and the community they lived in evolve and, in many ways, vanish before their very eyes.

Each represents the 10th generation of his family to have lived in Water Mill, Mr. Burnett’s family having been given its original 86 acres in 1646 in a land grant ordered by King Charles I of England. Despite his extended family’s sprawling history in East End farming, Mr. Halsey was born to a carpenter who was starting to piece together only enough land to raise the crops to feed his family.

When Mr. Halsey was just 17, and Abram was 21, the pair took over what had become a 90-acre potato farm during their childhood but found that the farming business on Long Island in the post-World War II era was going through a painful period of evolution.

“We carried on with potatoes, but we both got married, and we were losing money hand over fist,” Mr. Halsey recalled. “We tried every damn thing. We did peas and beans, but we had to take them to Riverhead to sell, and we wouldn’t get paid for six months. There was a time we thought cows was the way to go. We took them out to Sagaponack to graze … and they all got out down there, took us a week to round them up. No matter what we tried, it was the wrong thing. That’s when my brother quit. My kids were 12 to 14, so we figured we’d try the farm stand for a few years. It caught on.”

Mr. Halsey’s children and grandchildren today farm much of the same land his father accumulated. They grow more than 100 varieties of organic vegetables. “We’d never heard of some of the vegetables people wanted,” he said. “They’d come in and ask, and the next year we’d raise it.”

This season will be the first that Mr. Halsey hasn’t been on a tractor on a daily basis to help his kids with the family crops. Mr. Burnett, by contrast, is more than 50 years removed from a plow, and was the last farmer in his family. Early in his adulthood, he gave up the farming business he’d been raised into in favor of a blacksmith’s forge and a job “in town” to be more involved in the close-knit Water Mill community.

“You either stayed on the farm with your family, or you did business and got involved in the community,” Mr. Burnett recalled in the sun-drenched living room of his house, in the shadow of the hulking houses of Fordune Estates that now cover his family’s former farmland. “I wanted that feeling of independence—so long as I stayed on the farm there was somebody that was my boss: my father. But somewhere along the line, I got involved in the community. So I found this gentleman—Hildreth was his name—and I bought his blacksmith shop from him.”

As today’s farmers climb into monstrous air-conditioned harvesting tractors costing hundreds of thousands of dollars, to sow the seeds that will be this year’s harvest, Mr. Halsey and Mr. Burnett told tales of the old Water Mill schoolhouse and some of the very first farming vehicles—chain-drive trucks with hard rubber tires that “you could hear coming over Shinnecock Hills,” and a farm’s fleet of tractors, each designed for specific task, rather than a single vehicle towing interchangeable implements for specific chores.

“Cliff Foster has to get his son sometimes to start some of his equipment, I imagine,” Mr. Burnett chuckled, adding that he remembered a time when farms didn’t yet have the assistance of motorized tractors. “We’d get up at 6, 6:30, and start cranking, and you’d get one tractor started by 9:30 and you’d think you were going forward.”

Both remembered the bygone era fondly, despite its hardships and complications.

“We survived,” Mr. Halsey said.

“Yes, we did,” his friend reiterated. “We survived just fine.”